Kemba Walker is an NCAA champion and a four-time NBA All-Star. He also is a product of the Bronx. Those things, he believes, are inextricably linked.

Walker, who retired from playing pro basketball in July and joined the Charlotte Hornets coaching staff, is one of the last great New York City basketball stars. The city used to mass produce basketball players, but that pipeline has slowed to a trickle over the last decade.

The city still has talent, but it is leaving the five boroughs at an earlier age. While Walker remained in New York before he left for the University of Connecticut, his path is no longer the norm.

“That’s changed over the years,” Walker said.

Power Memorial Academy, which produced greats like Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and Len Elmore, closed in 1984. Rice High in Harlem — where Walker and other former college stars went — closed in 2011. Some of the area’s best players have flocked to New England and New Jersey schools.

Orlando Magic guard Cole Anthony left Archbishop Molloy in Queens for Oak Hill Academy in Virginia. Detroit Pistons forward Taj Gibson left Brooklyn for Stoneridge Prep in California. Philadelphia 76ers center Mo Bamba left the Bronx for Westtown School in Pennsylvania.

“There are still players that come (out of) New York, but the problem is so many of them leave,” said Ron Naclerio, the head coach at Benjamin N. Cardozo High School in Queens and the all-time winningest public school coach in New York history. “I hate that it’s happening,” he added.

Naclerio, and others, like Gibson, have been looking for solutions. Two New Yorkers want to make New York a hotbed for basketball once again.

Griffin Taylor and Jared Effron launched The Program intending to make New York City hoops good enough that up-and-coming players don’t need to leave. Their goal is to convert an empty warehouse in the Greenpoint section of Brooklyn into a state-of-the-art youth facility with a full-sized court and an adjacent weight room, hoping it helps.

“Statistically and reputationally, New York isn’t producing the talent at quite the rates that it used to,” Taylor said, “and so what Jared and I really wanted to solve for is the why.”

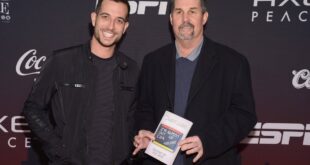

(Photo of The Program founders Griffin Taylor and Jared Effron: Courtesy of The Program)

Taylor and Effron grew up in the shadow of the New York Knicks and the St. John’s University teams of the 1990s. The sport has always been a part of the city’s DNA and spawned some of the best amateur and pro players in history, from Lew Alcindor to Kenny Anderson to Stephon Marbury.

Madison Square Garden might still be known as the mecca of the sport, but the city itself is no longer considered the epicenter by some.

The area’s college programs have struggled. The Knicks’ recent resurgence broke two decades of dysfunction and losing, but the 2023-24 team failed to end the franchise’s 51-year championship drought after falling to the Indiana Pacers in the Eastern Conference semifinals. The high school scene has regressed, and there’s been a talent drain out of the city. From 2020-23, per 247 Sports, there wasn’t a single top-50 recruit from a New York City high school.

“There’s really a divide between the pay-for-play and the AAU circuit,” said Effron, The Program’s co-founder and president. “I think there’s a big reason that we haven’t been able to develop kids: Because we’re not mixing that world together. I don’t know if this is a national problem, but I definitely see it here in New York.”

Gibson, who came up through the famed New York Gauchos AAU program, felt he had no choice but to leave. Gibson said his coaches were the ones who convinced him and his mother to go to the West Coast before his sophomore year of high school because they felt he needed to have a change of scenery from where he had grown up. When he arrived in California, first at Stoneridge Prep and then at Calvary Christian, he felt he had landed in another basketball ecosystem altogether.

“I’m out there and I’m seeing it’s a different lifestyle,” Gibson said. “These guys are basically already preparing to go to the pros. The way the workouts went, the way guys were carrying it. I don’t know if it was the weather … it was just a different kind of atmosphere.”

Added Rod Strickland, a Bronx native who played for the Knicks and is now the head coach at Long Island University: “Just like the NBA has gone global, our country, the U.S., has kind of caught up.”

Strickland used to be a prototypical New York City product, a lightning-quick point guard with a tight handle and flair. He said the city used to create players of a certain mold.

Naclerio believes it’s because there aren’t enough places for young players to play in the city anymore, and when they do, they’re working with trainers instead of in competitive games. One solution Naclerio suggested is for more top-flight indoor courts — he has nothing for disdain for the double-rims found in parks across New York City.

The Program is trying to close that gap by offering just that. It has grown slowly. Taylor and Effron incorporated The Program in late 2021 and started taking on partners in April 2022. Last spring, they left their full-time jobs and fully committed to getting The Program off the ground. Early on, it held several amateur events around the metropolitan area, attracting some of the best high school players from the state and neighboring New Jersey.

Last winter, The Program signed a lease for its first physical space, a 12,500-foot warehouse in the Greenpoint neighborhood of Brooklyn not too far from the East River and set to be a development home for some of the city’s talent. There are designs on one day housing its teams, too. They also have amassed a group of investors — including Walker, Chris Mullin and Carmelo Anthony — who believe in keeping New York City’s best young players in the city and helping them grow, much like they did.

Taylor and Effron hope to use The Program as a vehicle to help emerging players have a space and amenities to build their skills. Their facility will serve as a development academy and also could eventually lead to a basketball program. The duo has raised a little more than $4 million so far from investors, Taylor said, with the goal of raising $6 million total. Roc Nation is an investor, as are JJ Redick, Miles McBride and Moe Harkless.

The Program NYC has leaned on Ross Burns, a trainer for NBA players, to design its on-court agenda. It will hire coaches and instructors who have all at least played college basketball to implement it. NBA champion and Hall of Fame broadcaster Kenny Smith will serve as an adviser, as will grassroots staple Chad Babel and longtime New England high school coach John Carroll.

The Program will have annual membership plans, and it also intends to offer scholarships through a charitable trust for children. The facility is slated to open by June 2025, Taylor said.

It plans to make its gym available to the city’s AAU teams, and it wants to be a go-to option for NBA and WNBA teams and players who need a space to work out when they’re in town during the season or in the offseason. Taylor and Effron hope to have their own boys and girls teams, too, with Nike’s EYBL circuit as a destination.

(Renderings courtesy of The Program)

“There’s nothing better than being able to train and watch a pro train and emulate that,” Mullin said. If that’s something that can be a reality, that’s what it’s all about is passing on your knowledge, your daily work habits, and things like that to the younger generation. That’s really how you influence and impact, you know, the people behind you.”

Mullin, who went to high school at Power Memorial in Manhattan and then Xaverian in Brooklyn, said he felt he never had to leave. He stayed in New York and starred at St. John’s before building a Hall of Fame NBA career.

Gibson wants to bring back prominence and spot the disconnects that have hampered the basketball scene in the last decades. He believes it will take the whole community uniting again.

There is hope, and a belief from him and others, that it’s possible to get New York City back to where it was, even if it will be difficult.

“New York City is New York City, so there’s always a possibility,” Strickland said. “You can’t tell me there’s not talent.”

Anthony grew up in the Red Hook neighborhood of Brooklyn before moving to Baltimore at 8. The environment Anthony sees now as he guides his son, consensus four-star guard Kiyan Anthony, through the amateur basketball ecosystem, is one he wants to help.

“I’ve seen firsthand how access to the best gyms, training and coaching can accelerate development,” Anthony said in a statement to The Athletic. “To be able to provide accessible court space, and elite coaching and training under one roof to kids all across the city, it can only improve the collective talent pool coming out of New York.

“And if we can keep our most talented kids home instead of them leaving at younger ages to go to schools in other states and markets, it is a win for New York across the board.”

Taylor and Effron already have a plan for the future, too. If this goes as they hope it will, there also is room for growth. The Program owns the air rights in its current location and can build up on its current one-story operation. Eventually, the decision-makers could build out, too, and expand to other major cities across the East Coast.

Walker is the last product of NYC’s high school system to make an All-Star team; his last appearance was in 2020. Walker believes he would not have gotten to that point if he had not just been raised in New York City but also built his career there. He hopes The Program can create that path for others.

“I would like the same for the next generation of kids,” Walker said. “I feel like a lot of the kids don’t stay in the city to pursue their basketball career. I feel like this could be the opportunity to get them to stick around and to have someplace to go as a safety net and as a place to get better.”

(Illustration: Meech Robinson / The Athletic; photos: David Dow, Rich Schultz, Jean Catuffe / Getty Images)

Source link

meganwoolsey Home

meganwoolsey Home